By Dr. Luke Haydock (University of Guelph)

Hot on the heels of the release of the 4th volume of the Davis-Thompson Foundation’s Surgical Pathology of Tumors of Domestic Animals series, our global community of keen veterinary professionals waded into the complex world of bone tumors under the expert eye of Dr. Keren Dittmer. This webinar was delivered on November 13th (AEST) as part of the foundation’s Australian Webinar Series and it topped off a remarkable year of presentations by experts from around the world, kindly provided at antipodean-friendly times.

Throughout the course of this talk, Dr. Dittmer illustrated the value of a holistic approach in the diagnosis of bone tumors by integrating diagnostic imaging, cytology, and histology into a collaborative unit. This highly informative webinar served to encourage veterinary pathologists to broaden their scope beyond that of a microscope and, in the process, greatly improve the accuracy and efficiency in which they diagnose bone tumors.

The talk began with brief review of the various imaging modalities most widely available to veterinary professionals, and their respective pros and cons in the diagnosis of bone disease. By the end of this talk it was made abundantly clear to myself (and I’m sure many others in the audience) that the value of a set of high-quality radiographs accompanying a bone biopsy could not be overstated.

Likewise, Dr. Dittmer demonstrated that a complete cytological examination performed prior to or hand-in-hand with biopsies is also highly rewarding. Firstly, this more rapid and low-risk means of tumour sampling may provide veterinary diagnosticians with vital information that may preclude the need for incisional biopsies altogether. Additionally, unlike their formalin-fixed counterparts, cytological preparations are significantly more amenable to staining with reagents (i.e NPT/BCIP) that highlight cells, such as osteoblasts, which have high alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity. When applied to unstained cytological samples, this stain provides an optimally sensitive (100 %) and highly specific (89 %) indicator of ALP activity within cells. But user beware, neoplastic cells from chondrosarcomas and amelanotic melanomas are also occasionally ALP positive!

Considering the availability of adjunctive diagnostic techniques, by this point in the talk I certainly found myself asking, “is a bone biopsy always necessary?” – and indeed, Dr. Dittmer soon demonstrated that an incisional biopsy is not always a required step in the diagnosis of a bone tumour. Briefly, her advice on the matter was that if radiographic or cytological diagnostics are highly suggestive of an aggressive bone lesion (particularly in countries where fungal osteomyelitis is uncommon!), then an incisional biopsy may simply be an unnecessary expense on the way to eventual amputation / limb sparing surgery. Pathologists providing guidance to clinician’s regarding optimal incisional bone biopsy technique should be aware of the value of suggesting multiple sampling sites (taken from both the centre and leading edge of the lesion) and for suggesting that post-biopsy radiographs to be taken. These extra measures will serve to maximise the chances of the budding bone pathologist receiving a diagnostic sample.

As both the novices and experts among us will know, bone pathology is fraught with diagnostic challenges. Fortunately, Dr. Dittmer was here to guide us through some of the more common conundrums that give pathologists pause for thought. So, if you have ever found yourself asking any of the following 3 questions, I suggest you play close attention.

- Is this a reactive disease process or a neoplastic disease process?

As the audience was already made very aware, radiographs are indispensable in resolving this dilemma. A primary goal of the radiologist in the assessment of a bone lesion is to differentiate between an aggressive or benign bone lesion. The main features assessed to make this determination are the extent and pattern of periosteal reaction and medullary / cortical osteolysis. These features exist on a spectrum with the more ill-defined or poorly delineated appearances being suggestive of more rapid change and, thus, more aggressive disease (i.e. malignant neoplasia or osteomyelitis). This webinar included an excellent review of the radiological terminology, the patterns of periosteal reaction and osteolysis, and their respective correlation to benign or aggressive disease. Those with an interest in exploring this topic in more detail are highly encouraged to refer to Dr. Dittmer’s recent publication in the September 2021 issue of Veterinary Pathology (or watch Dr. Dittmer in action yourself on the Davis-Thompson Foundation YouTube channel! [Note: Seminar available until 15th December, 2021]). Another significant advantage of radiographs in the differentiation of reactive and neoplastic disease is the ability to monitor progression of disease over time. Rapid rate of change is unsurprisingly a hallmark of aggressive disease, whereas stable or resolving change over time may preclude the necessity for a biopsy altogether!

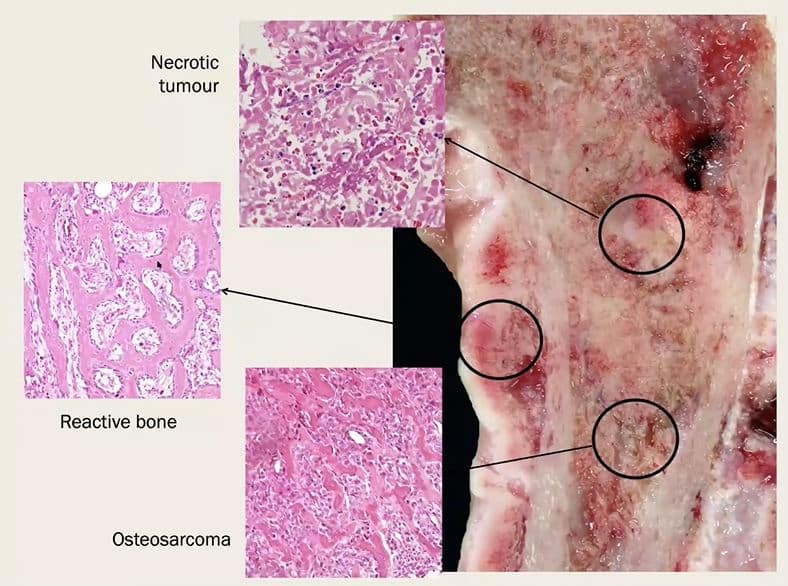

Wandering back into more familiar territory for most of us, Dr. Dittmer then shared with us the histological features that can assist the perplexed pathologist in making the vital differentiation between reactive and neoplastic disease. The characteristic features to keep an eye out include:

| Reactive Bone | Tumor Bone |

| Well-ordered maturation | Lack of orderly maturation |

| Woven bone deposited onto mature lamellar bone | Woven bone |

| Interconnected and gradually thickening bony trabeculae | Trabeculae do not interconnect in a orderly manner and are not connected to pre-existing lamellar bone |

| Intertrabecular spaces filled with loose mesenchymal tissue | Intertrabecular spaces are filled with pleomorphic mesenchymal cells +/- osteoid |

| A single layer of osteoblasts lining trabeculae | Neoplastic osteoplasts have frequent or atypical mitoses. |

| Bland osteoblasts and mesenchymal cells with no atypical mitoses |

But, like most things in life, its not quite that simple. Keep in mind that it is common for neoplastic disease to contain regions of reactive bone. Once again, radiographs are essential in guiding your decision in these times of uncertainty – Is your biopsy truly just reactive disease, even though the radiographs are suggestive of aggressive bone disease? Another biopsy may be in order. If post-biopsy radiographs were taken, are your biopsies likely to be a representative sample taken through the centre of the radiographic lesion? If not, another biopsy may be in order. Are follow-up radiographs showing rapid change despite your previous diagnosis of a reactive disease process? You guessed it, another biopsy may be in order.

- Is this a fracture callus or tumor bone?

As pathologists, it is not uncommon to find ourselves confronted with a need to differentiate a healing fracture site from a bone tumor. Both fracture calluses and tumor bone are characterised by populations of mesenchymal cells capable of synthesizing various types of bony and hard tissue matrix. Depending on the stage and dynamics of fracture healing, a fracture callus may be dominated by osteoblastic, chondroblastic, or fibroblastic mesenchymal cells, and it is incumbent upon the pathologist to differentiate these cells from those of an osteoblastic, chrondroblastic, or fibroblastic tumor. Adding a further element of complexity, the lesions of a pathological fracture may be superimposed upon those of a bony neoplasm – close scrutiny is often required in such cases. Indeed, it goes without saying that radiographs are immensely valuable in such scenarios, and it really needn’t take much radiographic expertise to vastly improve the accuracy of your pathologic interpretation.

Histologically, a main feature that may assist you in determining a fracture callus from a bone tumor is the organised and inwardly progressing maturation of matrix – however, this pattern of maturation may not always be appreciable on small incisional biopsies. In the absence of this latter feature, Dr. Dittmer suggests also keeping on the look out for these following features:

- Reactive osteoblasts with abundant cytoplasm and mild anisokaryosis

- No marked pleomorphism

- No atypical mitoses

- A single layer of osteoblasts lining trabeculae of woven bone

- Intertrabecular spaces filled by hypocellular mesenchymal tissue or granulation tissue

- Evidence of remodelling of necrotic bone

- Is this an osteosarcoma or another type of sarcoma of bone?

Much prognostic significance rests on the pathologist’s ability to accurately discern osteosarcomas from other sarcomas of bone. However, this is often easier said than done. Fortunately, Dr. Dittmer dedicated a significant portion of this highly informative webinar to walking us through some of the more common diagnostic conundrums. The following summaries simply skim the surface of Dr. Dittmer’s deep well of knowledge, and interested readers are highly encouraged to explore this discussion in more detail by accessing the rebroadcast of the webinar on our YouTube channel (https://youtu.be/VYJVXOZqbkw).

- Chondroblastic osteosarcoma vs chrondrosarcoma

- If you spot any osteoid, it is likely a chondroblastic osteosarcoma.

- Imaging: Flat bones (e.g. ribs, skull, pelvis, scapula) are sites of predilection for chondrosarcoma; long bones are sites of predilection for osteosarcoma.

- Cytology: NPT/BCIP stains can be of some value – however, up to 25 % of chondrosarcomas may be ALP positive.

- Telangiectatic osteosarcoma vs hemangiosarcoma

- The presence of any tumor bone should steer you towards a telangiectatic osteosarcoma – large biopsies may be necessary.

- Imaging: 78 % of primary appendicular hemangiosarcomas occur in the hindlimbs, compared to 31 % of telangiectatic osteosarcomas. Pulmonary metastases of hemangiosarcoma are typically miliary and poorly defined, compared to the well-defined nodular metastases of osteosarcoma. Hemangiosarcomas more likely to be accompanied by signs of pleural / pericardial effusion.

- Cytology: NPT/BCIP staining of smear for tumor cell ALP activity.

- Immunohistochemistry: A mainstay of tumor differentiation – Factor VII antigen or CD31 IHC readily identifies hemangiosarcomas.

- Giant cell-rich osteosarcoma vs giant cell tumor of bone

- Challenges arise in tumors with large numbers of giant cells and little to no osteoid.

- Imaging: Giant cell tumors of bone are usually located in the epiphysis and are predominantly lytic with no periosteal reaction and short zone of transition. These tumors can erode through cartilage and spread into joints, but do not commonly metastasise. Giant cell osteosarcomas are usually located in the metaphysis and have typical radiographic changes of aggressive disease; they rarely cross the joint.

- Cytology and IHC are of limited assistance due to both tumors containing cells of osteoblastic lineage.

- Fibroblastic osteosarcoma vs fibrosarcoma

- Issues arise in tumors with large amounts of collagenous matrix and no osteoid.

- Imaging: Fibrosarcomas are primarily lytic with little periosteal reaction. Fibroblastic osteosarcomas have typically aggressive features.

- Cytology: NPT/BCIP is indispensable – fibrosarcoma cells should not stain ALP positive. Encourage clinicians to collect cytological smears at time of biopsy!

Much to the delight of those in attendance, Dr. Dittmer also rounded out her discussions with ample opportunity for audience participation. As if we needed any more reason to pay close attention, there were several opportunities to participate in audience polls, and, for each diagnostic challenge, we had the chance to explore a highly practical and easy-to-follow case example.

On behalf of the Davis-Thompson Foundation, I would like to express my immense gratitude to Dr. Dittmer for taking the time out of her weekend to deliver this webinar to our global veterinary pathology community. The tireless efforts of the Davis-Thompson Foundation towards the global advancement of veterinary and comparative pathology would be sorely diminished without experts such as yourself who are willing to donate their time and expertise to the cause.