On the 26th February, 2022, the Davis-Thompson Foundation was privileged to host a highly informative and supremely entertaining presentation on inflammatory CNS diseases delivered by none other than the foundation’s president herself, Dr. Jey Koehler! We hope you enjoy this review written up by Dr. Haydock.

By Dr. Luke Haydock (University of Guelph)

Anyone who has had the opportunity to attend a Dr. Koehler presentation before will surely be familiar with her humorous stylings and boundless enthusiasm for all things veterinary pathology – and those traits were on full display as she took us on a 2-hour crash course through “a lot of bugs, a little bit of pugs, and absolutely no drugs”. Yes, it was a bit of a misleading title but, hey, at least it rhymes!

I personally found the structure of this talk to be very useful as it began with providing a solid grounding in the dynamics of inflammation that are unique to the central nervous system – an organ system that, for me at least, is unrivalled in its enigmatic and nebulous physiology and anatomy. Some of the “immuno-weird” features of the CNS include low levels of MHC-I expression, a comparatively very low rate of influx of leukocytes into the uninflamed brain (especially neutrophils), and the tightly regulated blood-brain barrier (BBB). The latter feature is a significant determinant in the ability of different pathogens, molecules, and cells to infiltrate the brain and cause inflammation. That being said, there are several areas where the BBB is lacking – such locations include the circumventricular organs, the pituitary gland / median eminence, rostral hypothalamus, area postrema, and pineal gland. Dr. Koehler also used this part of her talk to introduce the relatively recent concept of the glymphatic system (2013 is still recent right?!). While it was originally thought that the brain lacked lymphatic drainage, it turns out there is a “brain-wide” system of drainage which utilizes the perivascular channels formed by astrocytes. This glymphatic system represents an important means of waste clearance from the brain and also contributes to distribution of glucose, lipids, amino acids, and neurotransmitters throughout the brain. Interestingly, the glymphatic system is mainly only functional when we are asleep – an important thing to remember for all the pathology residents out there during your late-night study sessions! Dr. Koehler also spent some time outlining the central role that the meninges play in CNS inflammation. In health, the meninges represent one of the largest reservoirs of “traditional” inflammatory cells (e.g. macrophages, T and B lymphocytes, NK cells, mast cells, dendritic cells, etc.) in the CNS, and the dural venous sinuses are among the most active sites of immune surveillance in the CNS. As such, when an insult to the CNS occurs, it is likely that many of the inflammatory cells within the neuroparenchyma have arrived via initial recruitment into the meninges. Along with the dural venous sinuses, another major source of immune surveillance in the CNS is the extensive network of microglia. These innocuous cells, often ignored, may very well be the secret heroes of the CNS! Among their many other important functions, they are capable of sampling the entire extracellular space of the brain in the space of just a few hours!

Following this review of all the immune oddities that are unique to the CNS, Dr. Koehler then transitioned into what really gets us pathologists excited – diseases!

Any attempt to condense Dr. Koehler’s extensive review of inflammatory CNS disorders into a single blog post would likely result in this webinar review more closely resembling a chapter from a particularly dense textbook. In lieu of an extensive summary of each disease, I have decided to share with you a few fun facts or distinctive features of each disease that stood out to me while attending this riveting presentation.

Canine Distemper Virus (CDV)

Genus Morbillivirus, family Paramyxoviridae

- There are no less than FOUR different disease manifestations of CDV in dogs.

- These differ most in the signalment of the patient and the distribution of lesions:

- Classic disease in puppies

- “Back-to-front” severity of lesions

- Most severe in white matter and, to a lesser extent, the grey matter of the cerebellar folia, around the 4th ventricle, and spinal cord.

- Multifocal encephalitis in young adult dogs

- “Back-to-front”

- “Old dog encephalitis” in middle aged to older dogs (rare)

- “Front-to-back” – involves the cortex, usually spares the cerebellum and spinal cord.

- Post-vaccinal encephalitis with modified live viral vaccines (rare)

- Lesions centred on the brainstem grey matter (especially pontine nucleus).

- Classic disease in puppies

Canid alphaherpesvirus-1

Subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae, Family Herpesviridae

- Not “traditionally” thought of as a neurological disease in dogs as most puppies die of disease in other systems before developing CNS lesions.

- A great paper by Jager et al., 2017 highlights the CNS lesions in natural infections:

- Include glial nodules, lymphocytic meningeal infiltrates, and cerebellar cortical necrosis confined to the granular layer.

Rabies

Genus Lyssavirus, Family Rhabdoviridae

- The zoonosis that no pathologist wants to be surprised by!

- Keep an eye out for Negri bodies – however, they may be absent in up to 30 % of cases!

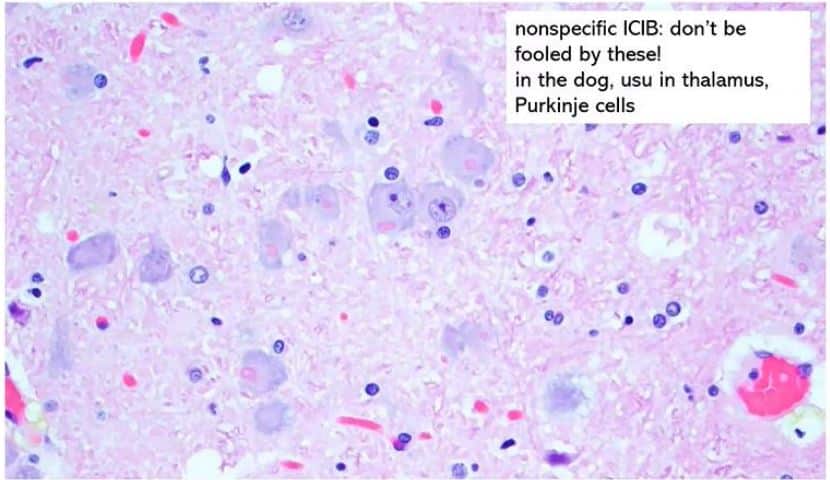

- Don’t confuse Negri bodies for non-specific inclusions seen in some species.

- In dogs, these are most common in neurons of thalamus and Purkinje cells.

- If there is no inflammation accompanying inclusions – less likely to be Negri bodies!

Pseudorabies (Suid herpesvirus-1)

Subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae, Family Herpesviridae

- OIE-listed notifiable disease!

- Dogs most commonly infected via direct contact with infected pigs or ingestion of uncooked infected pork.

- Many animals will have lesions of self-induced facial trauma due to intense pruritus (“mad itch”).

West Nile Virus

Genus Flavivirus, Family Flaviviridae

- Bird – mosquito cycle.

- Other animals are dead end hosts.

- Disease is most significant in horses and humans.

- Dogs are usually asymptomatic.

Eastern Equine Encephalitis

Genus Alphavirus, Family Togaviridae

- Bird – mosquito cycle.

- Other animals are dead end hosts.

- Most relevant as a pathogen of horses.

- In dogs, usually seen in puppies less than 6 months of age.

- Unlike other forms of viral encephalitis, may have a neutrophilic component to inflammation (especially in meninges)!

Bacterial Meningitis / Encephalitis

- Occurs sporadically in dogs – some of the most common isolates include Eschrichia coli, Streptococcus , and Klebsiella spp.

- Not usually a difficult diagnosis – predominantly neutrophilic inflammation.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

- Caused by Rickettsia rickettsii transmitted by tick bites.

- Most common in young dogs.

- Infects endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells – vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis.

- Organisms stain weakly with Gram – try Giemsa or Gimenez instead!

Ehrlichiosis

- Caused by Ehrlichia canis tranismitted by tick bites.

- Similar to Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever.

- However, inflammation is more plasmacytic.

- Morulae may be visible within CSF leukocytes.

Blastomycosis

- Primarily caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis.

- Remember your B’s – Blastomyces is big (10 – 25 μm), it’s blue, it has BAD1 (virulence factor), and it exhibits broad based budding!

Cryptococcosis

- Primarily caused by Cryptococcus neoformans and gatii.

- Does it look like the tissue is filled with soap bubbles? You may have a case of cryptococcosis on your hands!

- Large clear mucicarmine rich capsule around a 5 – 10 μm diameter yeast that exhibit narrow based budding.

Coccidiomycosis

- Primarily caused by Coccidioides immitis and posadasii

- Unlike other common fungal infections, which prefer moist, nitrogen-rich environments, Coccidioides prefer dry, dusty conditions.

- Southwestern United States is a hotspot!

- Spherules can resemble Blastomyces spores except:

- Larger (25 – 60 μm).

- Double-contoured wall.

- Replicate by endosporulation.

Histoplasmosis

- Primarily caused by Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum.

- CNS involvement is an uncommon consequence of dissemination from pulmonary disease.

- Small (2 – 4 μm) diameter, intrahistiocytic yeasts with a thin clear halo.

Phaeohyphomycosis

- Rare – a true zebra!

- Opportunistic infection caused by saprophytic dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi.

- Cladophialophora most common.

- 3 – 6 μm diameter, septate, variably to rarely branching, pigmented hyphae within discrete abscessed lesions.

Protothecosis

- Primarily caused by Prototheca zopfii.

- A saprophytic algae that causes opportunistic infections in immunocompromised dogs.

- 10 – 20 μm diameter sporangia that may be undergoing distinctive, wedge-shaped endosporulation (it looks like a Mercedes Benz logo!) within granulomatous meningoencephalitis.

Toxoplasmosis / Neosporosis

- Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum are ubiquitous protozoon pathogens that can cause a wide range of disease manifestations in several species.

- CNS lesions are primarily necrotising, vasculocentric, and lymphohistiocytic.

- Inflammation may occasionally be eosinophilic – if you see eosinophils, consider protozoa!

- Tachyzoites or bradyzoite cysts may be seen in section.

Free-living Amoebae

- The diseases that will make you never want to go swimming in warm freshwater ever again!

- Species such as Naegleria fowleri, Balamuthia mandillaris, and Acanthamoeba which invade the cribriform plate to cause severe necrotizing and pyogranulomatous meningoencephalitis.

- The organisms can look a lot like large macrophages – keep an eye out for 10 – 30 μm diameter, ovoid organisms with a central round nucleus and prominent central karyosome.

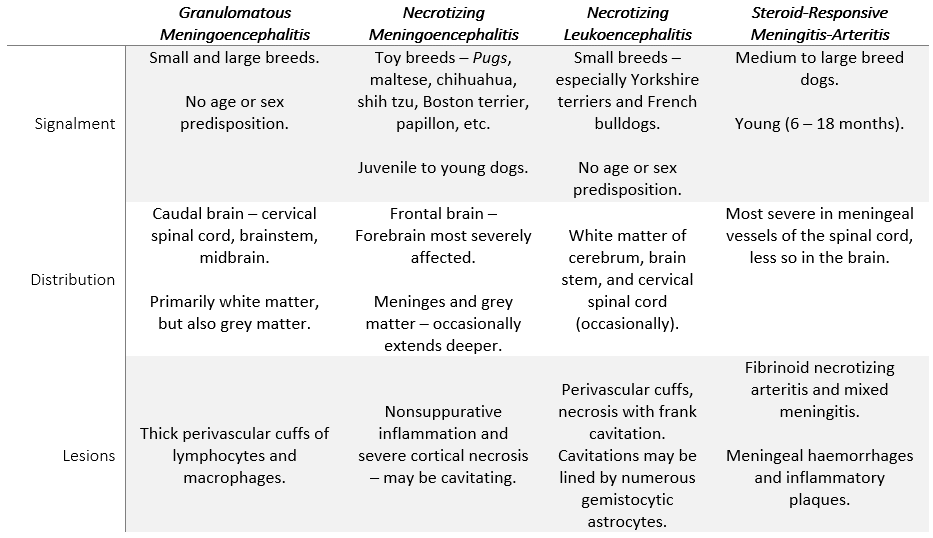

Dr. Koehler wrapped up her talk with a summary of the entities collectively known as the meningoencephalitides of unknown origin / etiology (MUOs / MUEs). Now I don’t know about you but I find keeping the differences between these entities straight in my mind to be a real headache (pardon the pun)! So, here is a handy table that summarizes some of the differences that were highlighted by Dr. Koehler.

Lastly, on behalf of the Davis-Thompson Foundation, I would like to extend my immense gratitude to Dr. Koehler for taking the time out of her busy schedule to provide the global veterinary community with this entertaining and informative seminar. I hope you all enjoyed this webinar review! Thank you!