Another in the series “Things I didn’t learn in the library”

By Roger Kelly

‘OK, who’s going to get the brain out?’

I had just put the question to a group of senior students and the duty pathology resident working on the autopsy on an adult Holstein dairy cow. We were in the large post mortem room of the prestigious New York State College of Veterinary Medicine within Cornell University, at Ithaca in upstate New York. In 2000 I had been invited to the Pathology department as a locum, to fill in for six months after a professor had resigned on short notice.

I was used to undergraduates looking at the floor and acting invisible when asked to volunteer for anything, so I turned to the resident. ‘Sheree, could you please show them how you expose brains here. Try and get one of them to do it.’ I addressed the undergrads, ‘Soon you’ll be doing this job out in a field somewhere, with an owner watching. You’ll want to be able to convince a farmer that you know what you’re doing.’

Sheree was looking embarrassed. Oh dear, she’s only just joined the department, hasn’t she? Now I’ve put her on the spot… She explained her discomfort: ‘Actually, Dr Kelly, we always get the techs to open the craniums. They’re so expert and very quick…’

My disbelief must have been obvious. ‘But for pity’s sake! Are you going to tell me that cattle veterinarians in the US aren’t expected to retrieve brains from field post-mortems? If they aren’t, who’s going to do it for them?’

I called one of the post-mortem room technicians over and explained my problem and asked for a hatchet, or, if that wasn’t available, a large handsaw.

Pat looked puzzled. ‘Well, gosh, we always open the heads for everyone, Doctor. We’ve got that special bandsaw all set up, and it only takes a moment…’ He shrugged. ‘Anyway, we don’t have a hatchet or a handsaw.’

Defeated, I watched him expertly open the cow’s cranium, and planned my next move.

Clive Huxtable, like me an Australian academic for hire, had been working for a few years at Cornell and was now in charge of the autopsy service. I’d known him for a long time – it was he who’d invited me to Cornell when the vacancy arose. When I told him of my dismay about the retrieval of large animals’ brains, he sighed, ‘Yes, Rog; I was horrified too, when I found out how they do things here. I’ve managed to get the youngsters to remove brains from small animals, but the OH&S crowd here are a nightmare. They’re terrified the bloody lawyers will bankrupt the school if a student gets injured in the PM room.’

‘At least someone should show them how easily it can be done, Clive,’ I grumbled. ‘We both had Bill Hartley instructing us during our course in Sydney. Didn’t he show you how to expose the brain with a cleaver? You know how it is with techniques. Once you’ve seen someone do something clever, you know it can be done and you’ll keep trying till you get it right.

Memories of my own trials were coming back to me. ‘When I got to the Queensland vet school, Hans Winter ran the PM room where he had a great big vise with teeth in its jaws. It was for holding cattle and horse heads firmly so he could use a big handsaw on the cranium. When I took over the diagnostic service I didn’t let students use it because they’d think that, when they’d graduated, they wouldn’t be able to take brains out in the field unless they had something like that. After I’d perfected Hartley’s technique I stopped using the saw on large animals and have been using the hatchet ever since.’

‘Well, if we can find a hatchet here somewhere, could you do a Hartley-style demo?’ ‘Too right I could, Clive. I’ll even sign an affidavit relinquishing all rights to sue Cornell if I injure myself.’

‘Weeks later when Clive was on PM-room duty, my office phone rang. ‘Clive here, Rog. We’re doing a big old dairy cow and we want its brain. And Pat’s brought a hatchet from his home. Could you come and show us your cranium-cracking trick?’

I was soon in the change-room and into overalls and rubber boots. There seemed to be rather more people in the PM room than I’d expected, so word must have spread that an entertainment had been organised.I had hoped to give a little run-down on sampling cerebrospinal fluid before removal of the head, but Pat, anxious to help, had already cut the head off and skinned it.

He had even removed the nose, which I regretted because the bovine nose is a handy handle. Oh, well; that’s show business. I was giving my little spiel about the advantages of what I was about to do, when I noticed Sandy de Lahunta at a dissection table across the room.

Professor Alexander de Lahunta was arguably the world’s most famous veterinary neuropathologist, and he was removing the brain from a rat that he suspected might have a pituitary tumour. He was clearly not going to let anyone use a bandsaw on that. And he was clearly also taking an interest in what I was up to. Just a little more creative pressure for me…

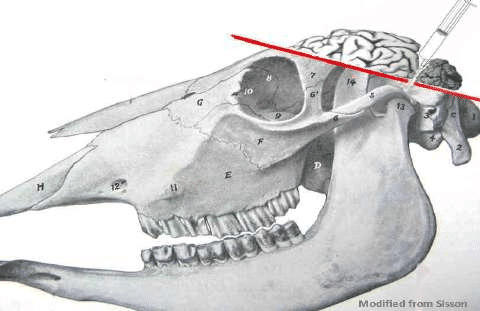

‘On with the show. I set about the cow’s skull with the hatchet, breaking through the frontal sinuses with vigorous strokes that soon had bone chips flying. Now’s the moment for the OH&S inspector to show up and panic about me not wearing a face shield…But I got through the rough work without any drama, and proceeded to more gently crack the inner table of the cranium.

Then I cut through the occipital ridge down to just above the occipital condyles, whereupon the cranial cap became loose, held only by the dura mater covering the brain. Since the noise of the attack had precluded commentary, I paused to explain what I’d done, then reversed the hatchet and aimed a shrewd blow at the back of the poll.

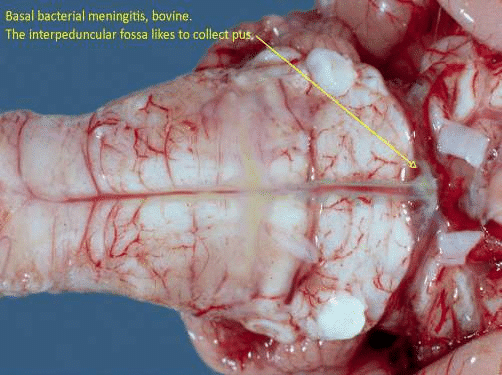

Demonstrations like these are of course prone to glitches, but I got away with this one. I was hugely gratified to see the cranial cap fly across the room, spinning over the tiled floor until it pulled up at de Lahunta’s feet. Sandy, famous as a showman, chimed in as if rehearsed. ‘Just bring that thing over here, will you, and get to work on this rat for me?’ After the laughter and applause, I showed how the dura should be removed without touching the brain surface, so that uncontaminated samples for bacteriology could be taken before removing the organ. Then I demonstrated how to use a syringe to aspirate the bacto sample from the interpeduncular fossa before removing the brain and immersing it in fixative solution.

Clive approached and murmured, ‘That couldn’t have gone better, Rog. I wouldn’t have liked to do that sort of show in front of a crowd.’

I grinned. ‘Sometimes you can be lucky. For God’s sake, though, don’t ask me to do another one in front of a mob like that.’

The glorious autumn colours of the Ithaca maples and pin oaks swirled in drifts on the lawns of the pretty campus, and then one evening it snowed on me as I walked back to the apartment. All too soon it was time to prepare for the trip home. I packed all the material I’d accumulated during my stay and just managed to get it down to airline weight, and crunched through the snow to my last Cornell workday.

Sheree knocked on my door that morning and said, ‘I hope you didn’t bring your lunch today. You’re coming downtown with us residents for lunch.

That was very sweet of them. The residents, from South America and Japan as well as North America, had been fun to work with. They were all striving to be diplomates of the American College of Veterinary Pathologists. The examinations for this are rigorous and they were much hungrier for pathology knowledge than were the undergraduates with whom I had worked so long.

The lunch was a jolly affair and a few amusing incidents were revisited, and then Sheree made a pretty little speech and presented me with a strangely-shaped, heavy package. As I accepted it, I knew what it was. A high-quality hatchet… far too heavy for the trip home. But it made a nice present with which to

thank Clive for getting me to Cornell.

Epilogue: in Feb. 2019, Richard Ploeg, who had done his pathology residency at UQ with me in the ‘90s, sent me a picture of one of his residents at that time (Dr. Carmen Lau), taken in the PM room of the Texas A&M veterinary school. You can imagine how happy this made me.