by Simon Spiro MA VetMB MVetMed DPhil

DipACVP FRCPath MRCVS

Wildlife Veterinary Pathologist

Zoological Society of London

Regent’s Park

As the pathologist for a 200-year-old zoo, I have seen my fair share of terrible post mortem reports, many of which do not have the excuse of having been written before the invention of the typewriter. While we are all familiar with the uselessness of descriptions like “hepatitis” or “lung lesions”, perhaps the most irritating are those where there has been an attempt at description, but you still have no idea what they have seen. If you see the words “Lung: Multifocal white nodules” do you picture three large, tumour-like masses, dozens of small, granuloma-like specks, or peripheral emphysema-like expansions?

I find that undergraduate students often struggle with description and can produce examples that are both overly long and omit key details. I believe that this is because we often focus descriptive teaching on adjectives (distribution, size, colour, texture etc.), students lose sight of the true purpose of description. Pathologic description is ultimately an exercise in empathy; what key features do I need to communicate so that you can picture a fair representation of what I am seeing?

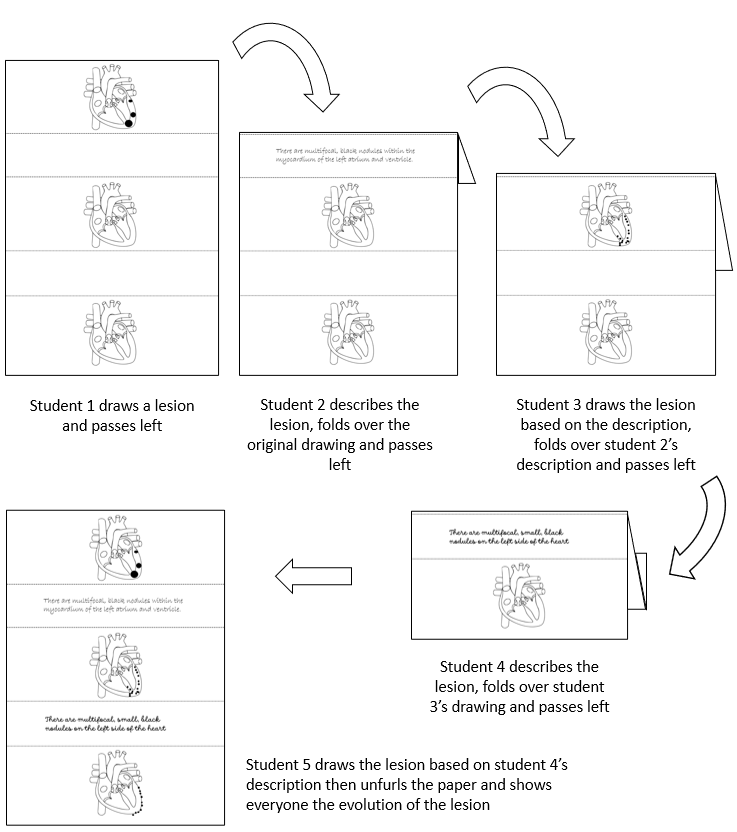

I have had some success teaching this concept of empathy through a parlour game that I used to play at university and have now learned, rather wonderfully and while writing this article, is known as Eat Poop You Cat. In the pathological version of the game, a group of at least five students are given sheets of paper on which are three identical outline drawings of organs separated by two boxes in which to write notes. The students each draw one or more lesions onto the top organ, then pass it to the student on their left who writes a description. The second student then folds over the original picture so that only the description is visible and passes it to student 3, who attempts to draw the lesion onto the second picture based on student 2’s description. Student 3 then folds over the description and passes their drawing to student 4 and the whole process is repeated. Once the fifth student has done the final drawing, the paper is unfurled and the drawings compared. If the descriptions have been well written, the top and bottom drawings should look very similar, but if they are in any way inadequate this should be quickly obvious.

In the example below, student 2 describes the lesion as “multifocal, black nodules within the myocardium of the left atrium and ventricle”. Because there is no indication of size and “multifocal” is relatively vague, student 3 interprets this as numerous small nodules rather that the three big ones that student 1 envisaged. Student 4 then describes the lesion as “multifocal, small, black nodules on the left side of the heart”. Because they have used the preposition “on” rather than “in”, student 5 interprets this description to mean that the nodules are epicardial rather than myocardial. Thus, three large myocardial masses become many small epicardial nodules.

I find it helpful to play the game two or three times in a row and watch as the pictures become more iteratively homogenous as the students learn how to better describe the lesions. As they get better at it, my students always seem to revel in drawing ever more fiendish lesions to try and catch their colleagues out. This not only helps students develop “descriptive empathy”; the fun of the game can foster a more playful, interactive atmosphere in pathology classes that carries forward into the more complex teaching to come.